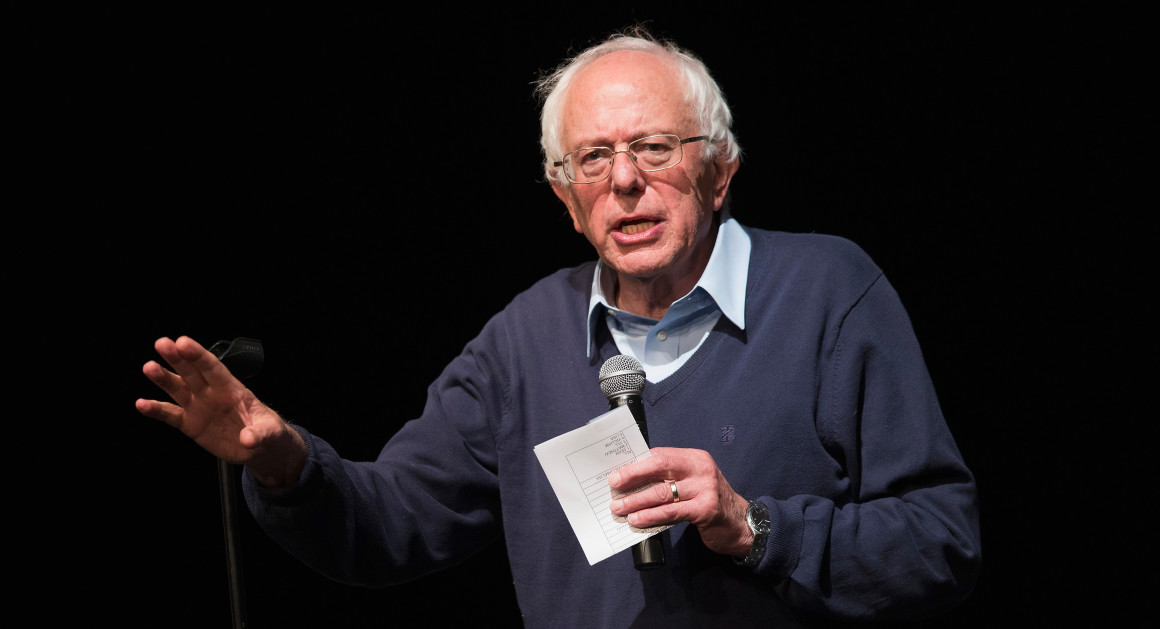

BALTIMORE — Bernie Sanders’ presidential prospects may be shrinking, but when he stepped off a campaign bus into the heart of this struggling city Tuesday, he was met by a spontaneous chorus of residents pleading for jobs and a pathway from poverty.

“You don’t want us to sell drugs,” one person yelled as Sanders – surrounded by a throng of cameras and local pastors – trudged past boarded up homes and businesses in the neighborhood where Freddie Gray was arrested in April before dying in police custody. Gray’s death set off a chain reaction of protests and, in some cases, violent recriminations that drew national attention to strained police-community relations.

For Sanders, the visit held manifold significance. He has struggled to connect with minority communities, which could stunt any momentum he gains if he manages to win early Democratic nominating contests in predominantly white Iowa and New Hampshire. Front-runner Hillary Clinton appears poised to dominate the other early contests and holds landslide-level leads over Sanders in national polling, as well as in surveys of African American voters.

The pastors and surrogates who flanked Sanders during his appearance here repeatedly insisted that the 2016 contender still has time to make inroads in their community before primary polls open.

“He’s a senator from Vermont that has an overwhelmingly white population. That’s not his fault," said Nina Turner, a former Ohio state senator who recently flipped her support from Clinton to Sanders and joined Sanders on the trail. “As he crisscrosses this country, people are going to hear his message and I believe that they’re going to respond to his message in the same way I did once I pulled back all the layers of what the status quo is and who I was supposed to support.”

Sanders’ trip also refocuses attention on Democratic primary rival Martin O’Malley, who was a Baltimore city councilor in the 1990s and a two-term mayor before he became Maryland’s governor in 2007. Though O’Malley is running a distant third in the contest, Sanders has criticized him more of late. A memo from the Sanders camp that surfaced before Thanksgiving criticized O’Malley for gaps in his immigration platform.

The governor's name didn’t come up during the event, and Sanders ignored a question shouted at him about O’Malley’s leadership as he departed.

Sanders kicked off his visit with a walking tour that quickly clogged city streets as curious residents trailed the horde of journalists following Sanders. The loop took him past the Penn/North metro station, the heart of where violent uprisings rocked the city after Gray’s death. Construction workers were actively repairing damaged buildings, some of which were adorned with signs reading “We must stop killing each other.”

Onlookers who recognized him quickly informed neighbors who he was until an impromptu crowd buzzed around the presidential hopeful. “We don’t want Trump,” one man yelled, referencing the Republican presidential frontrunner and attempting to lead nearby strangers in a chant. Others noted, not entirely disapprovingly, that Sanders was trying to “take down” Clinton.

Sanders and his entourage paused at a mural by the intersection where Gray was arrested to opine on dismal conditions of a neighborhood “less than an hour away from the White House.” He said the neighborhood looked more akin to one in “a third-world country” than a wealthy nation.

For the most part, Sanders stuck to a familiar script that he’s built into his stump speech, decrying soaring unemployment levels for African American youth, mass incarceration and the high school dropout rate.

He recited statistics about high unemployment for African American youths and decried the high school dropout rate. A press aide urged reporters to refrain from asking Sanders about ISIS, and Sanders showed a flash of anger when queried about the unexpected restriction.

“Of course I’ll talk about ISIS,” he said, his voice rising. “Today what we’re talking about is a community in which” half of the people don’t have jobs.” He said terrorism is a threat, but “so is poverty, so is unemployment.”

During a roundtable with pastors at the Freddie Gray Empowerment Center, Sanders called it “expensive to be poor,” emphasizing the lack of traditional banking options or affordable, quality food in low-income communities. His remarks appeared to be well-received, though pastors later emphasized that their words of approval should not be construed as an endorsement. Pastor Jamal Bryant, who represented the group of faith leaders who met with Sanders, noted that they’d also be meeting with Republican Sen. Rand Paul and hoped to arrange a meeting with Clinton within a few weeks.

In the meantime, though, Sanders soaked up praise from the assembled faith leaders. Pastor Greg James, of Florida, said he appreciated Sanders’ focus on restoring prisoner voting rights after they reenter the community, a passion he said stems from his own 14-year incarceration on conspiracy and drug charges.

“Every person who’s been turning back should be given a full opportunity to vote and be a part of society,” he said. “No taxation without restoration.”

Sanders’ event came at the same time he received the endorsement of the Working Families Party, the progressive group’s first-ever national endorsement. The group said Sanders overwhelmingly prevailed in a vote of its members, earning 87.4 percent support to Clinton’s 11.5 percent and O’Malley’s 1.1 percent.

Turner, the former Ohio senator, who ran a failed bid for secretary of state last year, said that if Sanders wins the nomination, he will be able to win Ohio where she lost because of the state’s more Democratic lean in presidential years.

“We delivered the presidency to Democrats twice, in 2008 and 2012,” she said. “In 2012, they said it couldn’t be done, that President Obama was on the ropes. But here comes Ohio and we delivered. When Senator Sanders fully gets engaged in the state of Ohio, people will hear that message.”

- Publish my comments...

- 0 Comments